EMILY WHANG / NEXTGENRADIO

What is the meaning of

home?

Sophie Diaz speaks with Aura Garduño about her experience as a recently naturalized U.S citizen. For Garduño, Florida has been home for over a decade, but being naturalized allows her to put down roots in a new way. She finds herself with a new sense of security in her home state, while still being able to share her culture and traditions.

New citizen, rooted in Florida, blooms at last in color

Listen to the Story

Click here for audio transcript

When you get naturalized, you get a folder that has the U. S. Constitution and the, like, the Declaration of Independence. And there’s a message from whoever’s the current president. So I had one that said “message from President Biden”. And it starts off with “my fellow American”. And I started crying.

It’s been 15 years and hearing, like “my fellow American”. That was insane.

My name is Aura Garduño. And I am a dual citizen of Mexico and the U.S. as of December 19th.

So for the longest time, my parents never wanted me to know our legal situation. My dad has never wanted me to live in fear of anything.

As much as I have tried to assimilate, as much as I have tried to do everything I can, like, in my power to blend in perfectly with the crowd, there will always be something that separates me or always was something that separated me. But I focused on history, like I focused on, like, American knowledge, the English language in particular; just because I wanted to make sure that all the normal things that perhaps would have made someone, I guess, identifiable would not be applied to me. So when people think of an immigrant, they would think of an accent, maybe. So I tried to do everything I could in my power to not create an accent.

Even if people don’t want me here, Florida’s my home.

We have a restaurant.

Sounds inside the restaurant

Hi, guys. Are we eating in or to go?

This is my family restaurant. It’s called Casa del Taco. This is our first and only restaurant, so it’s quite an experience we’ve gone through. Um, I either help out with serving or in the case of like English, like language barriers I also help out with my parents with like the administrative side.

Currently, I am having the great American experience of job searching.

When I visited the state department last year and I talked to some of the interns and some of the workers there, um, I had told them, I was like, Hey, this is my situation. This is what I want. Like, how do I do this? And they were like, oh yeah, you’re not getting anywhere without that citizenship.

Now I feel like the world’s my oyster. I just want everything new. I got new hair. I will hopefully be getting some sort of new government job.

My parents are trying to own a house. I moved into my first apartment. I want to have roots here so that I can continue building more stability now and with more security.

I feel entirely at home in Florida. The work I do goes into the community. And like anything that I can to try to help the state. If anything, I’ve actually been really upset at some of the orgs I used to work at that have pulled out of Florida because this is my home and I’m like why are you looking at us like a lost cause.

Florida is my home, and feelings of uneasiness from the past have thankfully faded away.

I’ve worked almost a decade in politics and government to the extent I’m allowed to, considering I’m not, I wasn’t a citizen before that.

But me registering to vote, I cannot begin to explain to you the feeling of wow! This is, I get to put something towards that when before I would have to say to people that when I would be canvassing and I have to tell people like, hey, I can’t vote, vote for me.

Be my voice. I have a voice now. That’s insane.

For Aura Garduño, obtaining her U.S. citizenship after 18 years of living in Florida allows her a newfound sense of security. Her updated status offers her the opportunity to create more permanent roots and be her authentic, colorful self.

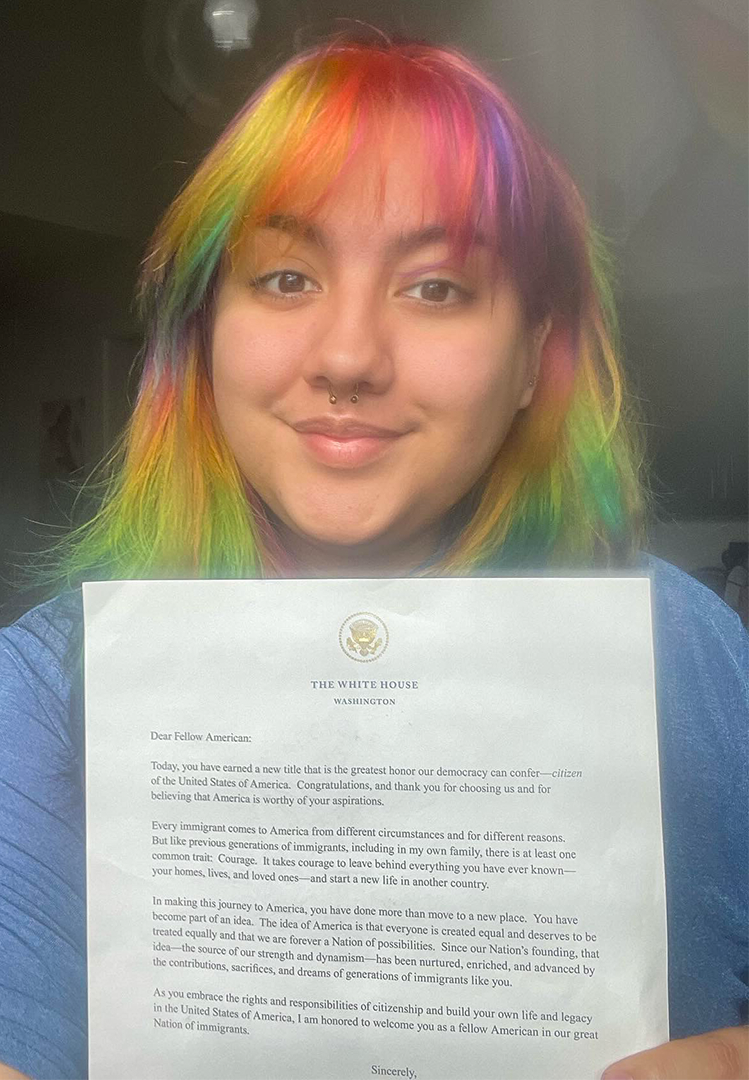

Aura Garduño was worried about a number of things the day of her naturalization interview and ceremony, but her hair was a priority both before and afterward. She tied her hair in a way that would hide her previous dye job, wore natural makeup, toned down the colors of her clothing and hid her piercings. Normally, Garduño is expressive with her outfits, pairing bold colors with bright makeup. She usually adds a small heart in eyeliner on her cheek.

“When I took my naturalization exam, I was terrified of any small thing,” Garduño said. “Maybe they think like, oh, we want, we don’t want this undesirable person to be a citizen, so we’re going to reject the application.” With a paper declaring her a citizen of the United States, Garduño has reclaimed her vibrant style.

“Now, I have rainbow hair.”

Aura Garduño stands in front of an alebrije she painted on a bathroom door of her parents’ restaurant. Alebrijes are a facet of Mexican folk art, also referred to as figuras.

SOPHIE DIAZ / NEXTGENRADIO

Garduño has lived in Florida since the age of 4, after moving from Mexico City with her parents. She’s 22 now and took the plunge to become an American citizen after holding a green card for three years. On December 19, 2023, Garduño took the civics exam and underwent her interview in Royal Palm Beach, Florida.

“It’s such a small room for what feels like such a[n] enormous step,” Garduño said.

As a young child, Garduño didn’t know her immigration status. She said her father took care to make sure she didn’t live in fear because of it. She remembers asking if she and her family were immigrants.

“And my dad’s like, yeah, but you’re fine,” she said.

Aura Garduño attends her naturalization ceremony in Royal Palm Beach, Fla., on Tuesday, Dec. 19, 2023. Garduño had previously been undocumented and is now a dual citizen.

PHOTO COURTESY OF AURA GARDUÑO

Aura Garduño brings drinks and chips to customers at her family’s restaurant on Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2024. Garduno works as a server at Casa Del Taco in Jensen Beach, Fla.

SOPHIE DIAZ / NEXTGENRADIO

Aura Garduño stands outside of Casa Del Taco on Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2024. Garduno says she enjoys sharing her culture by means of food.

SOPHIE DIAZ / NEXTGENRADIO

Despite her father’s efforts, Garduño became aware of her status and made a conscious effort to assimilate and avoid any typical stereotypes of immigrants.

“I focused on American knowledge, American history, the English language in particular,” Garduño said. “I tried to do everything I could in my power to not create an accent. I almost dropped my Spanish altogether.”

By the seventh grade, she could recite the presidents of the United States in order. Through middle and high school, she competed against students from other schools, answering questions based on American history in the Academic Games Leagues of America. Garduño took sixth place in the national competition and second place statewide. She took an interest in politics and international affairs, and volunteered by canvassing for a gubernatorial campaign and two efforts for the House of Representatives.

“People hate voting, I know they do. People hate politics, I know they do. But me registering to vote, I cannot begin to explain to you the feeling of ‘wow.’” Garduño said. “I get to put something towards that when before I would have to say to people — when I would be canvassing — and I’d have to tell people ‘Hey, I can’t vote, vote for me. Be my voice.’ I have a voice now. That’s insane.”

Garduño keeps the folder from her naturalization ceremony in her parents’ house. She said it contains copies of the U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence, along with a message from the current president.

“So I had one that said, ‘A message from President Biden.’ And it starts off with ‘My fellow American’. And I started crying,” Garduño said. “It’s been 15 years and hearing ‘My fellow American’ … I never thought we’d get here.”

Garduño’s lengthy wait isn’t an entirely unique experience.

According to U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services, non-citizens are required to spend at least five years as a lawful permanent resident or LPR. Depending on their birth country, non-citizen applicants face varied wait times. Applicants of Mexican origin spend an average of 12 and a half years as an LPR.

Garduño said she voices her concerns about American politics, but she hopes her peers don’t see her open criticism as hatred of the country.

“I want to improve the system … the system that has offered me and my family so much. I want it to be good. I want it to be better.”

So I had one that said, ‘A message from President Biden.’ And it starts off with ‘My fellow American’. And I started crying. It’s been 15 years and hearing ‘My fellow American’ … I never thought we’d get here.

Garduño said she feels she has come too far to leave Florida.

“I feel entirely at home in Florida,” Garduño said. “The work I do goes into the community. If anything, I’ve actually been really upset at some of the orgs I used to work at that have pulled out of Florida because this is my home. And I’m like, ‘why are you looking at us like a lost cause?’ Get back in here. We need to do the work.”

Within the last three years, Garduño has graduated from the University of Central Florida with a degree in political science and moved into her first apartment.

“Maybe it’s a Macbeth mentality of there’s no way of turning back now after everything that’s happened.”

Garduño splits her time between Orlando and Jensen Beach, where her parents own a Mexican restaurant and she works serving a few nights a week. She also helps with administrative duties when her parents run into any language barriers. She said the restaurant is decorated “as Mexican as possible.” Most of the furniture is sourced from her parents’ home, and the multicolored alebrijes (figures commonly incorporated into folk art) on the restroom doors were painted by Garduño.

Her family has taken large steps to cement its place in Florida, including her parents’ effort to purchase a home, her recent move and her family’s business, Garduño said. “Florida’s my home, even if people don’t want me here.”

Garduño has a newfound sense of security after her ceremony. “And I think, if anything, that’s, that’s what home is, you know? The feeling of being safe, the feeling of having structures, of having roots.”

Aura Garduño keeps the documents from her naturalization ceremony at her parents’ house. Among those documents is a letter she received from President Biden, addressed to “Dear Fellow American.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF AURA GARDUÑO

And I think, if anything, that’s, that’s what home is, you know? The feeling of being safe, the feeling of having structures, of having roots.