YUNYI DAI / NEXTGENRADIO

What is the meaning of

home?

Miranda Camp speaks with native New Yorker Sonya Mallard about her struggles to find a sense of home in Florida. Mallard grew up in Harlem and moved south in 1999 with her family to care for her husband’s grandmother. It wasn’t until Mallard found the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Complex in Mims, Florida, that she found her place. In 2013, she became the cultural coordinator for the center, where she keeps the Moores’ civil rights legacy alive.

From New York to Florida: one cultural coordinator finds purpose in keeping civil rights history alive

Listen to the Story

Click here for audio transcript

Sonya Mallard: I truly believe I found a home. ‘Cause a home is not just a physical location, it’s the memories, the experiences. And every person that come through that door, I treat them just like family, right?

My name is Sonya Mallard. I’m the Cultural Center coordinator at the Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Memorial Park and Museum.

It’s the cultural center and epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement. We teach people about the legacy of the Moores.

Harry T. Moore was truly a man before his time. He knew he had a target on his back. And he went every day, with the courage, knowing at any moment his life could have been just snuffed out, right? Um, which it was eventually on December 25th, 1951. However, he made every day matter.

I almost feel like their spirits are here. I really feel like for everything that took place is sacred ground, right?

I believe there’s so many voices crying from those graves and from the ground and from, um, the unspoken words that were never said that I have to make them proud. I get emotional, but I want them to really understand that that baton was passed and somebody’s running the race.

I’m a three time cancer survivor.

What I found when you get a diagnosis, I call it the big C, it changes you from the inside out, right?

It makes you realize the sun is really yellow and the birds really do chirp, right? You look at the things that you normally would have taken for granted. That it becomes that much more real.

So then you realize the world is much bigger than you, right? It’s not about you. So it’s not even about the big C anymore. It’s about what legacy you’re going to leave behind. Who are you going to help? And it changed my life.

Especially as someone who grew up in New York City and made the move to Florida. It’s an interesting change, a cultural change, and it’s given me a new perspective on what home truly means.

In 1999, my husband and I and my children packed up. Um, we sold our house and we moved to Florida to take care of his grandmother, who was 95 at the time. And I wanted to show my children, that’s what you do for family, right?

When I first came to Florida it was 50 years behind time. I was in a culture shock, right? And I used to cry. I wanted to go back and then when I found this place, it made me feel like my sense of purpose.

It’s still people on this very street with different values, but we still meet in a common place, and I believe our doors are always open.

Because we have nothing to hide. It’s so important that people understand that it’s just so much bigger than me or anyone else. It’s the legacy of the Moores, and it would never, ever die.

New York’s bustle will always be a part of Sonya Mallard. She was born and raised in Harlem, living and breathing the city’s hustle for decades.

“It was a sense of community, culture, diversity that meant the most to me,’’ said Mallard.

It was in New York where Mallard, 63, faced her first cancer diagnosis, which would become a two-decade long battle.

But despite that strong connection to the city, in 1999, she and her family packed up and moved over 1,000 miles south to Florida to care for her husband’s 95-year-old grandmother.

“I wanted to show my children, that’s what you do for family, right?’’ Mallard said. “You can get another house. You can get another couch, another television, but you can’t get another great-grandmother or grandmother. So I wanted to show them what the sense of family is all about.”

Sonya Mallard, the cultural coordinator of the Moore Cultural Complex, sits in front of a collage of the Moores in the museum’s lobby. Mallard works to maintain the legacy of the couple’s impact on civil rights in Florida and the country. Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2023.

MIRANDA CAMP / NEXTGENRADIO

She now makes her home in Titusville, 40 miles from Orlando on Florida’s east coast. There, it was hard for Mallard to adjust to a slower pace of life. She was used to a New Yorker’s sense of urgency.

“Everything that I do, I feel like I have to not just pace, but sprint, right?’’ Mallard said.

Mallard remembers the moment she knew she had transitioned from being a New Yorker to a Floridian. The moment came in the middle of traffic. She said that one day she was speeding down the U.S. Highway 1 in Titusville when she encountered a slow driver and did what most New Yorkers do — honk her horn.

“It was this little bitty, older lady,’’ Mallard said. “Her head was just above the steering wheel, and you could tell that I startled her, I scared her. And my heart sunk. I remember saying, ‘Sonya, what are you doing? Calm down … you’re not in New York. You in Florida, girl. Appreciate nature. Stop.’ I never blew my horn again. I promise you.’’

The walls of the museum serve as the timeline of the Moores’ and Central Florida’s civil rights history from 1860–1960. Visitors can walk along the timeline to learn about the Moores’ contributions to the civil rights movement through the years. Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2023.

MIRANDA CAMP / NEXTGENRADIO

Mallard’s sense of home in Florida deepened in 2013 when she discovered the Moore Cultural Complex in Mims, Florida, near Titusville. She was facing her third battle with cancer when she stumbled upon the complex and visited for the first time.

Inside, she learned the story of Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore and the work they accomplished in Central Florida for the civil rights movement in the 1940s and 50s.

“This was like a diamond in the rough. It was right after chemo. I had the scarf on, no hair, you know, I was still trying to figure out what I was going to do and I used to come out here and I was like, ‘Oh my God, this big building, so much rich history.’”

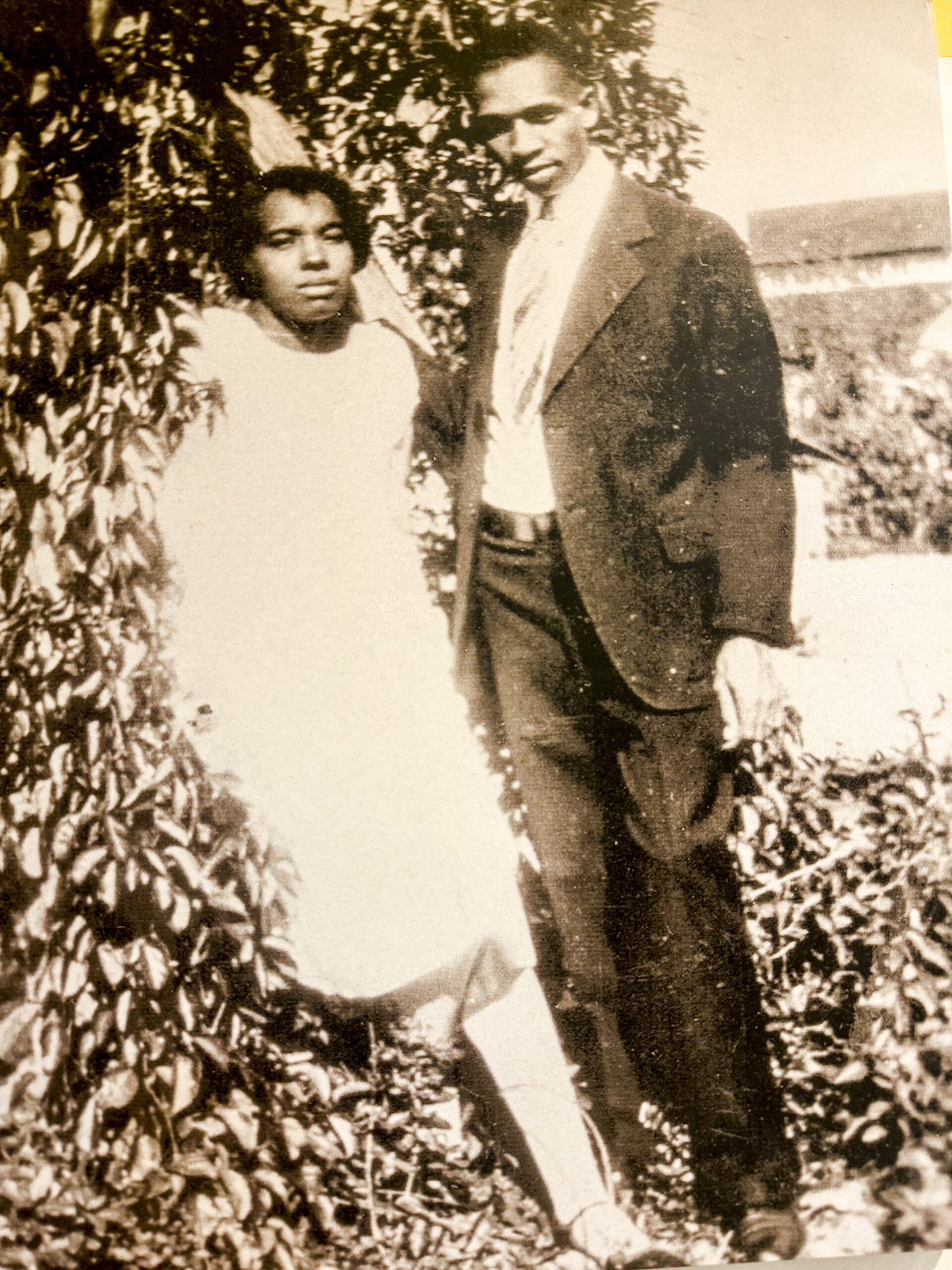

Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore were school teachers in Brevard County who fought for equal pay for Black teachers and voting rights for Black people in Florida. They became America’s first martyrs in the civil rights movement when they were killed by terrorists in their home in Mims on Christmas Day 1951.

MIRANDA CAMP / NEXTGENRADIO

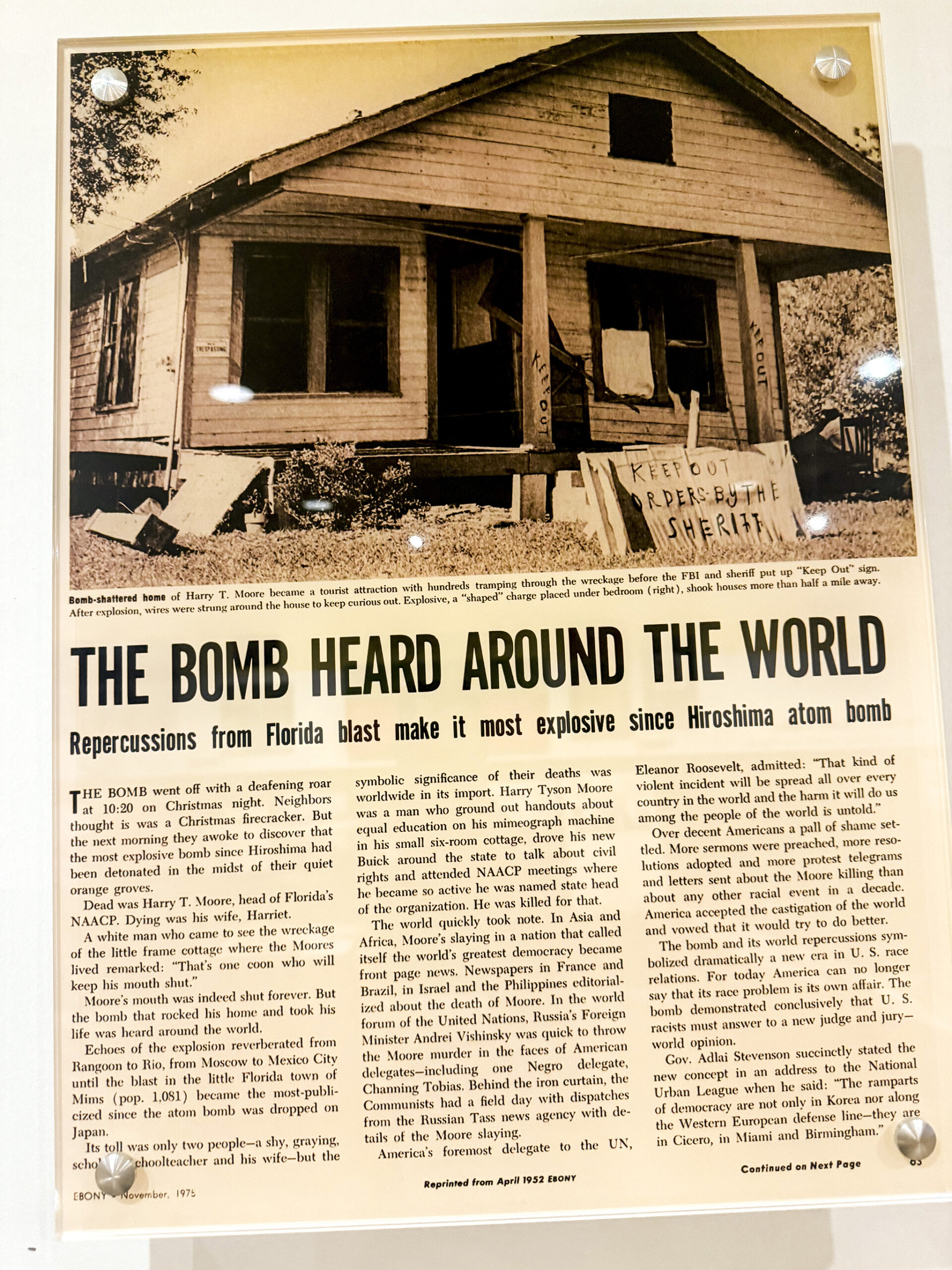

The bombing of the Moores’ home and their murders made headlines in newspapers and magazines across the nation and the world, including this article from the April 1952 issue of Ebony magazine, headlined, “The Bomb Heard Around the World.”

MIRANDA CAMP / NEXTGENRADIO

The Moores were school teachers in Brevard County and fought for the right of Black people to vote and for equal pay for Black teachers. On Christmas Day in 1951, which was also their wedding anniversary, they were sleeping in their home in Mims when terrorists crept under the floorboards of their bedroom and ignited a bomb. Harry Moore was killed immediately. Harriette Moore died from her injuries a few days later.

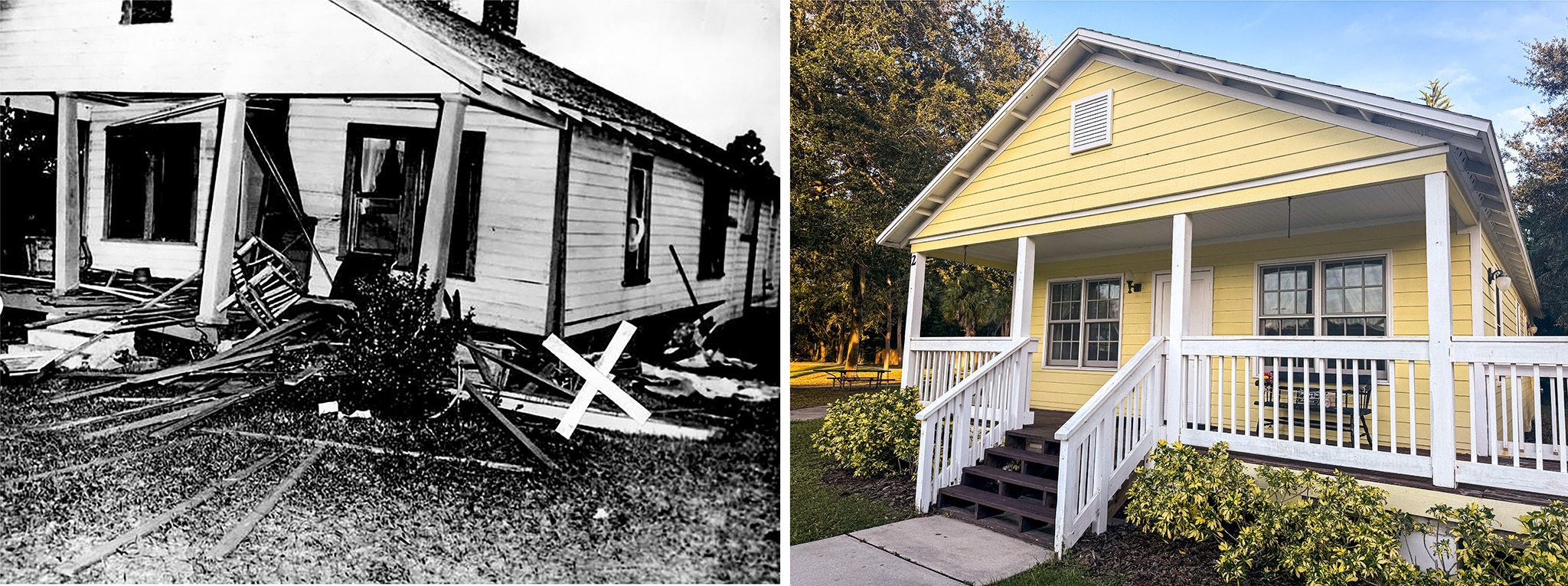

The Moore Cultural Complex now stands on the original property and includes a replica of the Moores’ home before it was dynamited and destroyed. The home and the center serve as a tribute to their sacrifice in the struggle for equal rights.

On Christmas night in 1951, terrorists bombed the Moores’ home while the couple and their family were sleeping. Today, a replica of the home sits on the original site of the Moores’ property so visitors can tour what the home looked like before the bombing.

MIRANDA CAMP / NEXTGENRADIO

ARCHIVAL PHOTO COURTESY OF FBI

Today, Mallard serves as the cultural coordinator and takes care of daily operations in the museum. She said that it has given her a new sense of purpose.

“I truly believe I found a home,’’ Mallard said. “Cause a home is not just a physical location. It’s the memories, the experiences, and every person that comes through that door, I treat them just like family.”

That includes the people who work at the center. Kecia Williams, an assistant at the Moore Complex, has known and worked with Mallard since 2005. She said Mallard is always checking in with co-workers to make sure they are okay.

“She really cares about your feelings,’’ Williams said. “She cares about you as a person. … Even if you don’t have family, you know what, you feel like you have family with her.’’

For Mallard, her home is now taking care of the Moores’ home — and their legacy.

“I have to make them proud. I have to, and I get emotional, but I want them to really understand that that baton was passed and somebody’s running the race.”

The Moore Cultural Complex sits at the end of Freedom Avenue in Mims, Fla. The street is named for the cause for which the Moores fought and died. Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2023.

MIRANDA CAMP / NEXTGENRADIO